Here is an article I discovered regarding BDSM and American College education. I don't think in the UK, we're anywhere near discussing it in our universities.

Scholars in Bondage

By Camille Paglia

Once confined to the murky shadows of the sexual underworld,

sadomasochism and its recreational correlate, bondage and domination, have

emerged into startling visibility and mainstream acceptance in books, movies,

and merchandising. Two years ago, E.L. James's Fifty Shades of Grey, a British

trilogy that began as a reworking of the popular Twilight series of vampire

novels and films, became a worldwide best seller that addicted its mostly women

readers to graphic fantasies of erotic masochism. Last December, Harvard

University granted official campus status to an undergraduate bondage and

domination club. In January, Kink, a documentary produced by the actor James

Franco about a successful San Francisco-based company specializing in online

"fetish entertainment," premiered at the Sundance Film Festival.

Three books from university presses dramatize the degree to

which once taboo sexual subjects have gained academic legitimacy. Margot

Weiss'sTechniques of Pleasure: BDSM and the Circuits of Sexuality (Duke

University Press, 2011) and Staci Newmahr's Playing on the Edge: Sadomasochism,

Risk, and Intimacy (Indiana University Press, 2011) record first-person

ethnographic explorations of BDSM communities in two large American cities.

(The relatively new abbreviation BDSM incorporates bondage and discipline,

domination and submission, and sadomasochism.) Danielle J. Lindemann's

Dominatrix: Gender, Eroticism, and Control in the Dungeon (University of

Chicago Press, 2012) documents the world of professional dominatrixes in New

York and San Francisco.

These books embody the dramatic changes in American academe

over the past 40 years, propelled by social movements such as the sexual

revolution, second-wave feminism, and gay liberation. It seems like centuries

ago that, as a graduate student in 1970, I was vainly searching for a faculty

sponsor for my doctoral dissertation, later titled Sexual Personae, which

was—hard to imagine now—the only project on sex being proposed or pursued at

the Yale Graduate School. (Rescue finally came in the deus ex machina of Harold

Bloom, whose classes I had never taken. Summoning me to his office, Bloom

announced, "My dear, I am the only one who can direct that

dissertation!") Finding a teaching job in that repressive climate proved

even more difficult. By the mid- to late-1970s, however, the gold rush was on,

as women's studies programs mushroomed nationwide, partly as a quick-fix

administrative strategy to increase the number of women faculty on

embarrassingly male-heavy campuses.

Today's market for sex topics is wide open. Major university

presses balk at little these days, short of apologias for paedophilia or

bestiality, and even those may be looming. However, despite the refreshing candour

displayed by the three books under review, a startling prudery remains in the

way their provocative subjects have been buried in a sludge of opaque theorizing,

which will inevitably prevent these books from reaching a wider audience.

Weiss, Newmahr, and Lindemann come through as smart, lively women, but their

natural voices have been squelched by the dreary protocols of gender studies.

It is unclear whether the grave problems with these books

stemmed from the authors' wary job manoeuvring in a depressed market or were

imposed by an authoritarian academic apparatus of politically correct advisers

and outside readers. But the result is a deplorable waste. What could and

should have been enduring contributions to both scholarship and cultural

criticism have been deeply damaged by the authors' rote recitation of

theoretical clichés.

Margot Weiss, a product of the department of cultural

anthropology and the women's studies program at Duke University, is an

assistant professor of American studies and anthropology at Wesleyan

University. In her absorbing portrait of San Francisco as "a queer Sodom

by the sea," Weiss surveys the gradual transformation of BDSM from the

"more outlaw" era of gay leathermen in Folsom Street bars of the

pre-AIDS era to today's largely heterosexual scene in affluent Silicon Valley,

where high-tech workers congregate at private parties or convivial

"munches" at chain restaurants with convenient parking lots. During

her three-year fieldwork, Weiss became an archivist for the Society of Janus,

which was founded in San Francisco in 1974 as America's second BDSM-support

group. (The first was the Eulenspiegel Society, founded three years earlier in

New York.) She also enrolled in "Dungeon Monitor" training, where she

learned safety guidelines for "play parties," including proper use of

whips and floggers and the adoption of a "safe word" to terminate

scenes.

Margot Weiss, a product of the department of cultural

anthropology and the women's studies program at Duke University, is an

assistant professor of American studies and anthropology at Wesleyan

University. In her absorbing portrait of San Francisco as "a queer Sodom

by the sea," Weiss surveys the gradual transformation of BDSM from the

"more outlaw" era of gay leathermen in Folsom Street bars of the

pre-AIDS era to today's largely heterosexual scene in affluent Silicon Valley,

where high-tech workers congregate at private parties or convivial

"munches" at chain restaurants with convenient parking lots. During

her three-year fieldwork, Weiss became an archivist for the Society of Janus,

which was founded in San Francisco in 1974 as America's second BDSM-support

group. (The first was the Eulenspiegel Society, founded three years earlier in

New York.) She also enrolled in "Dungeon Monitor" training, where she

learned safety guidelines for "play parties," including proper use of

whips and floggers and the adoption of a "safe word" to terminate

scenes.

Weiss's colourful cast of characters includes Lady Thendara

and her husband, Latex Mustang, who spend virtually all their spare time and

considerable income on an elaborate BDSM lifestyle. Mustang insists, "It's

no different than owning a boat." We meet "Francesca, a white, bisexual

pain slut bottom in her late 40s," and "heteroflexible" Lily,

age 29, who "identifies as a bottom/sub." Uncle Abdul, an electrical

engineer in his 60s, "identifies as a bi techno-sadist."

Weiss lists but avoids detailing BDSM practices, which range

from the benign (spanking, "corsetry and waist training") to the

grisly ("labial and scrotal inflation"). We also hear about

"incest play" and the baffling "erotic vomiting." Weiss

attended workshops in "Beginning Rope Bondage," "Hot Wax

Play," and "Interrogation Scenes" (Spanish Inquisition, Salem

witch trials, uniformed Nazis). Her "all-time favourite workshop

title": "Tit Torture for an Uncertain World."

Equipment for BDSM activities can be acquired as pricey

customized gear at specialty shops. Quality handcrafted floggers run from $150

to $300, while a zippered black-leather body bag goes for $1,395. But even

ordinary objects, such as table-tennis paddles, can be adapted as "good

pervertables." Home Depot is sometimes dubbed "Home Dungeon" for

its tempting offerings, such as rope, eye bolts, and wooden paint stirrers,

which we are told make "great, stingy paddles." The thrifty take

note: Rattan to make canes can be cheaply purchased in bulk at garden-supply

stores.

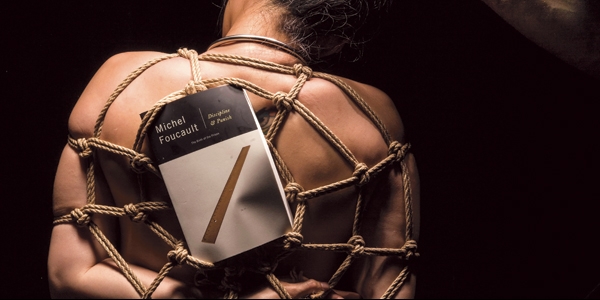

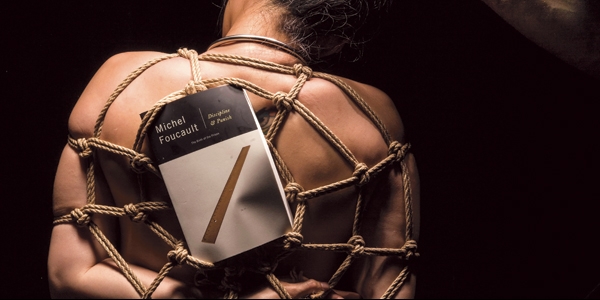

A recurrent problem with Weiss's book is that, despite its

claim to be merely descriptive, it is full of reflex judgments borrowed

wholesale from the current ideology of gender studies, which has become an

insular dogma with its own priesthood and god (Michel Foucault). Weiss does not

trust her own fascinating material to generate ideas. She detours so often into

nervous quotation of fashionable academics that she short-shrifts her 61

interview subjects, who are barely glimpsed except in a list at the back.

One feels the pressure on her to bang the drum of a

pretentious theorizing for which she has little facility and perhaps no real

sympathy. There are clunkers: "These binaries rely on the social

construction of risk." And howlers: "In what follows, I unfold the

thickness of such loadedness." Or this résumé of the circular thinking of

Judith Butler, the long overrated doyenne of gender studies: "In Butler's

work, intelligibility provides a horizon of recognition for subjectivity

itself, within which all subjects are either recognizable or unrecognizable as

subjects." Weiss speaks of her own "positionality" and

"Foucauldian framework," but she seems unaware that Foucauldian

analysis is based on Saussurean linguistics, a system of contested and indeed

dubious validity for interpreting the untidy realm of physical experience. As

for Butler, there are few signs in her work that she has yet done the

systematic inquiry into basic anthropology and biology that academe should

expect from theorists of gender.

Furthermore, Weiss is lured by the reflex Marxism of current

academe into reducing everything to economics: "With its endless

paraphernalia, BDSM is a prime example of late-capitalist sexuality"; BDSM

is "a paradigmatic consumer sexuality." Or this mind-boggling

assertion: "Late capitalism itself produces the transgressiveness of

sex¬—its fantasized location as outside of or compensatory for alienated labour."

Sex was never transgressive before capitalism? Tell that to the Hebrew captives

in Babylon or to Roman moralists during the early Empire!

The constricted frame of reference of the gender-studies

milieu from which Weiss emerged is shown by her repeated slighting references

to "U.S. social hierarchies." But without a comparative study of and

allusion to non-American hierarchies, past and present, such remarks are facile

and otiose. The collapse of scholarly standards in ideology-driven academe is

sadly revealed by Weiss's failure, in her list of the 18 books of anthropology

that most strongly contributed to her project, to cite any work published

before 1984—as if the prior century of distinguished anthropology, with its

bold documentation of transcultural sexual practices, did not exist.

Gender-theory groupthink leads to bizarre formulations such as this, from

Weiss's introduction: "SM performances are deeply tied to capitalist

cultural formations." The preposterousness of that would have been obvious

had Weiss ever dipped into the voluminous works of the Marquis de Sade, one of

the most original and important writers of the past three centuries and a

pivotal influence on Nietzsche. But incredibly, none of the three authors under

review seem to have read a page of Sade. It is scandalous that the slick,

game-playing Foucault (whose attempt to rival Nietzsche was an abysmal failure)

has completely supplanted Sade, a mammoth cultural presence in the 1960s via

Grove Press paperbacks that reprinted Simone de Beauvoir's seminal essay,

"Must We Burn Sade?"

Weiss is so busy with superfluous citations that she ignores

what her interviewees actually tell her when it doesn't fit her a priori

system. Thus any references to religion or spirituality are passed by without

comment. She also refuses to consider or inquire about any psychological aspect

to her subjects' sexual proclivities, no matter how much pain is inflicted or

suffered. She declares that she rejects the "etiological approach":

Any search for "the causation of or motivation for BDSM desires"

would mean that "marginalized sexualities" must be "explained

and diagnosed as individual deviations." To avoid any ripple in the smooth

surface of liberal tolerance, therefore, flogging, cutting, branding, and the

rest of the menu of consensual torture must be assumed to be meaning-free—no

different than taking your coffee with cream or without. (These books

approvingly quote BDSM players comparing what they do to extreme but blatantly

nonsexual sports like rock climbing and sky diving.) Weiss's neutrality here

would be more palatable if she were indeed merely recording or chronicling, but

her own biases are palpably invested in her avoidance of religion and her

moralistic stands on economics.

Staci Newmahr, an assistant professor of sociology at

Buffalo State College, did her ethnographic research in a "loud, large

Northeastern metropolis" that she mysteriously calls "Caeden."

The city has five SM organizations, three public "play spaces," and

three private dungeons for play parties. Newmahr went "deeply

immersive" in Caeden: While informing everyone that she was a researcher,

she also became a participant, taking the alias "Dakota" and logging

over a hundred hours a week in the SM scene. (Newmahr prefers the term

"SM" to "the newer and trendier" BDSM.) Members of the SM

community in Caeden are less affluent than those in Weiss's Bay Area sample but

just as overwhelmingly white. Newmahr did 20 "loosely structured"

interviews, which included off-topic conversation. Her portraits are sharply

observed and represent a significant contribution to contemporary sociology.

Newmahr captures how her subjects, even before they entered

SM, viewed themselves as "outsiders" who lived "on the fringe of

social acceptance." Most are overweight, but it's never remarked on.

Several women are over six feet tall, generally a social disadvantage

elsewhere. Newmahr gets answers from her subjects to questions about the past

that Weiss never asked: Some men are small-statured or have vivid, angry

memories of being bullied at school. Newmahr notes the "pervasive social

awkwardness" in the scene, the "ill-fitting, outdated clothing"

and the women's lack of makeup and jewellery. The men often have little

interest in sports and own cars of middling quality.

In describing her subjects' style of "blunt

speaking" and boasting, as well as their disconcerting invasion of

personal space in conversation, however, Newmahr does not mention social class,

about which she says little in her book. I would hazard a guess that she was

uncovering the difference between lower-middle-class and upper-middle-class

manners—the latter characterizing the world she customarily inhabits as an

academic. These fine distinctions are insufficiently observed in the United States,

where liberal political discourse too often employs a simplistic dichotomy

between rich and poor. Both Weiss and Newmahr observe how often their subjects'

casual conversations focus on science fiction or computer software. But Newmahr

shows superior deductive skills when she connects this to the Caeden

community's "affinity for complicated techniques and well-made toys."

Where Weiss sees only rank consumerism, Newmahr recognizes an operative

aesthetic of "geekiness as cool."

Despite her wealth of assembled data, Newmahr still stumbles

into the weeds of academic theory. We get "hermeneutic" this and

"hegemonic" that and trip over showy obstacles like "discursive

inaccessibility." There are empty phrases ("As Foucault illustrated

so powerfully") as well as a lockstep parade of the usual suspects, like

the automatically venerated Butler. Even more troublesome are Newmahr's semi

fictionalized sections, which she posits as intrinsic to the genre of

"auto-ethnography": "The postmodern view of ethnography as a jointly

constructed narrative rather than an accurate objective depiction of social

reality has gained support in recent years." Her accounts are "not

necessarily verbatim" but "edited or blended, resulting in

representations not entirely true to time and space simultaneously"; they

are "creative representations of authentic experiences."

But is this questionable practice defensible in scholarly

terms? The postmodernist slide away from the search for factual truth

undermines the entire raison d'être of universities and the professors who

ought to serve them. It is cringe-making that students are being fed this

postmodernist gruel: History is a narrative; every narrative is a fiction;

objectivity is impossible, so who cares what's real and what's not? Newmahr declares,

"All ethnographic work is on some level 'about' the ethnographer" (a

claim that begs for refutation). Peculiarly, she then decides to exclude her

own personal responses to her SM experiences because it might invite voyeurism.

But she can't have it both ways, fictionalizing her material (inescapably

"about" her) and yet arbitrarily concealing herself.

Where this diffidence becomes unsettling and even alarming

is in Newmahr's graphic descriptions of scenes she witnessed or participated

in. The first night she enters an SM club, she sees a woman in a nurse's

uniform "quietly nailing a man's scrotum to a wooden board," as he

"hissed and screamed." Newmahr was "taken aback" by this

horrific spectacle but tells us nothing more.

Newmahr's refusal to comment on this activity, to which I

would apply a term like "barbaric" (a concept evidently falling

outside the anesthetized world of academic theory), becomes even more glaring

when the object of abuse is herself. On one occasion, she lies on a bed in a

deserted apartment, where a stranger straddles her and presses a thick cord on

her throat until her breathing nearly stops; he smashes her in the face again

and again with the back of his hand and draws a razor blade across her cheek.

Except for a momentary panic at her isolation and potential danger, we learn

nothing of her reaction. Newmahr's flat affect, always disconcerting, becomes

positively chilling when she says of a sadist and masochist indulging in

"edgeplay": "Only the bottom is risking her life, and only the

top is risking a prison sentence."

Despite its defects, this book contains tantalizing

possibilities for a more flexible approach to gender studies. At times, Newmahr

uses theatre metaphors like "social scripts," derived from Erving

Goffman, the great Canadian-American sociologist whose work in such pioneering

books as The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959) was one of Foucault's

primary and deviously unacknowledged sources. Newmahr intriguingly describes SM

as "improvisational theatre," where "observers drift from scene

to scene" and where the performers must act as if the audience is not

there. But this excellent train of thought is not followed or developed.

Like Weiss, Newmahr tries to evade making judgments: She

shies away from "the ultimately unhelpful questions about whether SM is or

is not deviant sex." Nevertheless, she comes close to a breakthrough at

the very end of her book, when quoting a Caeden resident who sees SM play as a

way "to connect with the animalistic part of our beings." But because

nature and biology are erased from the Foucauldian worldview, with its strict

social constructionism, that hint is not followed up on. Post structuralism is

myopically obsessed with modern bourgeois society. It is hopelessly ignorant of

prehistoric or agrarian cultures, where tribal rituals monitored and invoked

the primitive forces of nature.

When she acutely declares that "issues of power are at

the core of SM play," Newmahr is unable to progress, because the only

power that exists for post structuralism resides in society—which every major

religion teaches is limited and evanescent. In the absence of knowledge of the

historical origin and evolution of social hierarchies, Newmahr ends up with

strained conclusions—for instance, that in the structured play of SM "the

erotic is desexualized," which is absurd on the face of it. Her own

hunches are more reliable, as when she rightly calls SM "a carnal

experience"—without realizing she has broken a law of the claustrophobic

Foucauldian universe, where nothing exists except refractions of language and

where the body is merely a passive recipient of oppressive social power.

Danielle Lindemann, who earned her doctorate in sociology

from Columbia University, is a research scholar at Vanderbilt University.

Dominatrix has vibrant passages of sparkling writing that demonstrate

Lindemann's talent and promise as a culture critic. Her personality charmingly

surfaces even in the acknowledgments, where she hails the "giant, cheap

margaritas" at the Dallas BBQ chain as "influential in the successful

completion of this project." Her knack for compelling scene-setting is

shown at the start of the very first chapter:

One night, I realize I've accidentally stepped on a man

rolled up in a carpet. We're at a Scene party in the basement of a restaurant

in New York's East Village. I approach the bar and put my foot on what I assume

is a step, when I hear a faint "Oof!" The man is laid out in front of

the bar, fully submerged in the rug, his face peering out of a roughly cut hole.

I step off and apologize, but I am immediately "corrected" by a

nearby domme.

"That's okay, sweetie—he likes it!" She proceeds

to kick the carpet repeatedly and with great force in her platform boots, while

the other people at the bar look on with a mixture of nonchalance and delight.

The man in the rug beams the whole time. I return to the table where I've been

sitting.

"I just accidentally stepped on a guy rolled in a

rug," I tell the group of people who've brought me to the party.

"Carpet Guy's here?" one responds.

Lindemann adroitly positions herself as a respectful but

bemused observer, like Alice in a perverse Wonderland. Unlike Weiss and

Newmahr, she maintains her professional objectivity and atonement to ordinary

social standards by preserving her outsider's stance and declining to become a

participant in the world she is studying. Lindemann is brisk and discerning as

she explores the world of professional dominatrixes ("pro-dommes"),

mainly in New York but also in San Francisco. Pro-¬dommes, who call their work

spaces "dungeons" or "houses" (short for "houses of

pain"), are rarely "full service," that is, providing sex.

Instead they cater to a broad range of tastes and desires, which Lindemann

organizes into three types: "pain-producing dominant, non-pain-producing

dominant, and fetishistic."

Requested scenarios include smothering (categorized with

choking as "breath play"), mummification (encasing in plastic wrap

and duct tape), infantilism (a man put in diapers), "splash" (playing

with messy food like creamed corn or pies), animal transformation (a man

becoming a puppy or pony), "French-maid servitude" (a man donning a

maid's uniform to clean house), "prison/interrogation fantasies," and

"secret-agent/hostage fantasies." Rarities reported by Lindemann

include a "leprechaun fetishist" and a client "aroused by a

Hillary Clinton mask."

The audacious voices of Lindemann's pro-dommes fairly leap

off the page. These fierce women have a haughty sense of métier. "I will

not recite dialogue," they proclaim on their Web sites. To bossy customer

demands, one pro-domme replies, "I am dominant. You are submissive. You

serve me."

Another instantly rejects any client who says, "I

want." She insists on "etiquette, protocols," and hangs up on

callers who fail to show due respect. It is proper for prospective clients to

begin, "Mistress, I want to serve you. My enjoyments are ... "

Pro-dommes often call their payment a "tribute"

rather than a fee, as if they were sovereign nations or celestial divinities.

In written correspondence with Lindemann, some pro-dommes habitually

capitalized "Me." What comes strongly across is the mystique surrounding

pro-dommes, with their special expertise and their disdainful separation from

the world of prostitution. The Internet, rather than magazines, has become the

preferred advertising medium. One pro-domme says flatly, "Print is dead.

Nobody who can afford to see me doesn't have a computer."

Another of Lindemann's disarming chapter openings: "I'm

sitting in a basement dungeon in Queens, and the first thing I notice is the

cheerleading outfit emblazoned with the word 'SLUT' hanging on the back of the

door." What a marvellous book this would have made had Lindemann sustained

that clear, engaging, reportorial style! But as in everything blighted by post

structuralism these days, we soon hit the obscurantist shallows. We hear about

the "dialectical process," "instantiation," "discursive

constitutions," and that dread phenomenon, "normative, gendered

tropes." Insights about drag are credulously attributed to Butler that

were basic to discussions 40 years ago of transvestism in Shakespeare's

comedies and that were soon superseded by David Bowie's avant-garde experiments

with androgyny in music and fashion.

As this book began to veer astray, I felt that Lindemann's

mind was like a sleek yacht built for exhilarating grace and speed but

commandeered by moldy tyrants for mundane use as a sluggish freighter. Her book

is woefully burdened by the ugly junk she is forced to carry in this uncertain

climate, where teaching jobs are so scarce. The very first paragraph of her

acknowledgments shows what has happened to this and countless other academic

books: Lindemann effusively thanks a Princeton professor "for giving me

the idea that Bourdieu may have had something to say about pro-dommes' claims

to artistic purity." Well, the dull Pierre Bourdieu, another pumped-up

idol forced on American undergraduates these days, had little useful to say

about that or anything else about art, beyond his parochial grounding in French

literature and culture. (No, Bourdieu did not discover the class-based origin

of taste: That was established long ago by others, above all the Marxist

scholar Arnold Hauser in his magisterial 1951 study, The Social History of

Art.) The leaden Bourdieu chapters bring Lindemann's momentum to a humiliating

halt and effectively destroy the reach of this valuable book beyond the dusty corridors

of academe.

Lindemann stays cautiously neutral about the acrimonious,

long-running debate among feminists over whether sadomasochism is progressive

or reactionary. But she so distracts herself with paying due homage to academic

shibboleths that she doesn't pursue her own leads—as when a San Francisco

pro-domme describes what she does as "performance art." Lindemann

should have investigated the genre of performance art as it developed from the

1960s and 70s on (thanks to Joseph Beuys, Yoko Ono, Eleanor Antin, and Bowie),

which would have given her a superb cultural analogue. She notes pro-dommes'

ability to "create environments" and separately draws a very striking

parallel to the Stanislavski theory of actors' total identification with their

characters. But neither of these exciting ideas is fleshed out.

Buried in a footnote at the back is a glimmer of what could

have made a sensational book: Lindemann says that pro-dominance "may have

more in common with other theatrical pursuits than with prostitution."

"I was recently struck to find, during a visit to the Barnard College

library," she writes, "that the books about strippers were sandwiched

between texts relating to pantomime and vaudeville, while the texts about

prostitutes inhabited a different aisle." Yes, modern burlesque was in

fact born in the 1930s and 40s in vaudeville houses that had gone seedy because

of competition from movies. Lindemann was poised to place pro-dommes' work into

theatre history—a tremendous advance that did not happen.

The lamentable gaps in the elite education that Lindemann

received at Princeton and Columbia are exposed in her two-page "Appendix

C: Historical Context," which is an unmitigated disaster. Two millennia

since ancient Rome are surveyed in the blink of an eye, and we are confidently

told, on the basis of no evidence, that the professional dominatrix is "a

fundamentally postmodern social invention." Sade and Leopold von

Sacher-Masoch (author of the 1870 SM novel Venus in Furs) are mentioned in passing,

but only via an academic book published less than a decade ago. There is no

reference to the immense prostitution industry in 19th-century Paris, where

flagellation was called "le vice anglais" (the English vice) because

of its popularity among brothel-haunting Englishmen abroad.

All three books under review betray a dismaying lack of

general cultural knowledge—most crucially of so central a work as Pauline

Réage's infamous novel of sadomasochistic fantasy, The Story of O, which was

published in 1954 and made into a moody 1975 movie with a groundbreaking

Euro-synth score by Pierre Bachelet. The long list of items missing from the

research backgrounds and thought process of these books is topped by Luis

Buñuel's classic film Belle de Jour (1967), in which Catherine Deneuve dreamily

plays a bored, affluent Parisian wife moonlighting in a fetish brothel. Today's

formalized scenarios of bondage and sadomasochism belong to a tradition, but post

structuralism, with its compulsive fragmentations and dematerializations, is incapable

of recognizing cultural transmission over time.

These three authors have not been trained to be alert to

historical content or implications. For example, they never notice the medieval

connotations of the word "dungeon" or reflect on the Victorian

associations of corsets and French maids (lauded even by Oscar Wilde's Lady

Bracknell). It never dawns on Weiss to ask why a San Francisco slave auction is

called a "Byzantine Bazaar," nor does Newmahr wonder why the lumber

to which she is cuffed for flogging is called a "St. Andrew's cross."

To analyze the challenging extremes of contemporary sexual

expression, one would need to begin in the 1790s with Sade, Gothic novels, and

the Romantic femme fatale, who becomes the woman with a whip in Swinburne's poetry

and Aubrey Beardsley's drawings and turns into the vampires and sphinxes of

late-19th-century Symbolist art, leading directly to movie vamps from Theda

Bara to Sharon Stone. And where is Weimar Berlin in these three books?

Christopher Isherwood's autobiographical The Berlin Stories, set in a doomed

playground of sexual experimentation and decadent excess, was transformed into

a play, a musical, and a major movie, Cabaret (1972), which has had a profound

and enduring cultural influence (as on Madonna's videos and tours). The

brilliant Helmut Newton, born in Weimar Berlin, introduced its sadomasochistic

sensibility and fetish regalia to high-fashion photography, starting in the

1960s. Weimar's sadomasochism and transvestism as portrayed in Luchino Visconti's

film The Damned (1969) helped inspire British glam rock. Nazi sadomasochism was

also memorably re-dramatized by Dirk Bogarde and Charlotte Rampling in Liliana

Cavani's The Night Porter (1974).

Where is the Velvet Underground? The menacing song

"Venus in Furs," based on Sacher-Masoch's novel, was a highlight of

the group's debut 1967 album. On tour with the Velvets that same year, Mary

Woronov did a dominatrix whip dance with the poet Gerard Malanga in Andy

Warhol's psychedelic multimedia show, the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. Other

SM motifs have woven in and out of pop music: a brutal bondage billboard on Los

Angeles's Sunset Strip for the Rolling Stones' 1976 album, Black and Blue, was

taken down after fierce feminist protests; dominatrix gear and attitude were

affected onstage by Grace Jones, Prince, Pat Benatar, and heavy-metal

"hair" groups like Mötley Crüe.

I was very disappointed to see Xaviera Hollander go

unmentioned. That vivacious Dutch Madame's feisty memoir, The Happy Hooker

(1971), detailing her bondage and fetish services, sold 15 million copies

worldwide. But there is no excuse whatever for the absence in these books of

Tom of Finland, whose prolific drawings of priapic musclemen formed the

aesthetic of gay leathermen following World War II. And the most shocking

omission of them all: Tom's devotee, Robert Mapplethorpe, whose luminous

homoerotic photos of the sadomasochistic underworld sparked a national crisis

over arts funding in the 1980s. Yet our three authors and their army of advisers

found plenty of time to parse the meanderings of every minor gender theorist

who stirred in the past 20 years.

These books never manage to explain sadomasochism or sexual

fantasies of any kind. In addition to its rejection of biology, post

structuralism has no psychology, because without a concept of the coherent,

independent individual (rather than a mass of ironically dissolving

subjectivities), there is no self to see. One of the numerous flaws in

Foucault's system (as I argued in my attack on post structuralism, "Junk

Bonds and Corporate Raiders," published in Arion in 1991) is his inability

to understand symbolic thought—which is why post structuralism is such a clumsy

tool for approaching art. But without a grasp of symbolism, one cannot

understand the dream process, poetic imagination, or the ritual theatre of

sadomasochism, with its symbolic psychodramas. Freud's analysis of guilt and

repression, as well as his theory of "family romance," remains

indispensable, in my view, for understanding sex in the modern Western world.

Surely current SM paradigms carry some psychological baggage from childhood,

imprinted by parents as our first, dimly felt authority figures.

The mystery of sadomasochism was one of the chief issues I

investigated in Sexual Personae (Yale University Press, 1990). My interest in

the subject began with my childhood puzzlement over lurid scenes of martyrdom

in Catholic iconography, notably a polychrome plaster statue in my baptismal

church of a pretty St. Sebastian pierced by arrows. I traced the theme

everywhere from flagellation in ancient fertility cults through Michelangelo's

neoplatonic bondage fantasy, "Dying Slave," to the surreal poems of

Emily Dickinson, whom I called "Amherst's Madame de Sade." I speak

simply as a student of sexuality: I have had no direct contact of any kind with

sadomasochism—except that I once had an author photo taken in front of a purple

velvet curtain in the waiting room of a dungeon in a midtown Manhattan office

building (which may be the very one where Lindemann's book begins).

In researching sadomasochism, I did not begin with a priori

assumptions or with the desire to placate academic moguls. I let the evidence

suggest the theories. My conclusion, after wide reading in anthropology and

psychology, was that sadomasochism is an archaic ritual form that descends from

prehistoric nature cults and that erupts in sophisticated "late"

phases of culture, when a civilization has become too large and diffuse and is

starting to weaken or decline. I state in Sexual Personae that "sex is a

far darker power than feminism has admitted," and that its "primitive

urges" have never been fully tamed: "My theory is that whenever

sexual freedom is sought or achieved, sadomasochism will not be far behind."

Sadomasochism's punitive hierarchical structure is

ultimately a religious longing for order, marked by ceremonies of penance and

absolution. Its rhythmic abuse of the body, which can indeed become

pathological if pushed to excess, is paradoxically a reinvigoration, a

trancelike magical realignment with natural energies. Hence the symbolic use of

leather—primitive animal hide—for whips and fetish clothing. By redefining the

boundaries of the body, SM limits and disciplines the over expanded

consciousness of "late" phases, which are plagued by free-floating

doubts and anxieties.

What is to be done about the low scholarly standards in the

analysis of sex? A map of reform is desperately needed. Current discourse in

gender theory is amateurishly shot through with the logical fallacy of the

appeal to authority, as if we have been flung back to medieval theology. For

all their putative leftism, gender theorists routinely mimic and flatter

academic power with the unctuous obsequiousness of flunkies in the Vatican

Curia.

First of all, every gender studies curriculum must build

biology into its program; without knowledge of biology, gender studies slides

into propaganda. Second, the study of ancient tribal and agrarian cultures is

crucial to end the present narrow focus on modern capitalist society. Third,

the cynical disdain for religion that permeates high-level academe must end. (I

am speaking as an atheist.) It is precisely the blindness to spiritual quest

patterns that has most disabled the three books under review.

The exhausted post structuralism pervading American

universities is abject philistinism masquerading as advanced thought.

Everywhere, young scholars labour in bondage to a corrupt and incestuous

academic establishment. But these "mind-forg'd manacles" (in William

Blake's phrase) can be broken in an instant. All it takes is the will to be

free.

Margot Weiss, a product of the department of cultural

anthropology and the women's studies program at Duke University, is an

assistant professor of American studies and anthropology at Wesleyan

University. In her absorbing portrait of San Francisco as "a queer Sodom

by the sea," Weiss surveys the gradual transformation of BDSM from the

"more outlaw" era of gay leathermen in Folsom Street bars of the

pre-AIDS era to today's largely heterosexual scene in affluent Silicon Valley,

where high-tech workers congregate at private parties or convivial

"munches" at chain restaurants with convenient parking lots. During

her three-year fieldwork, Weiss became an archivist for the Society of Janus,

which was founded in San Francisco in 1974 as America's second BDSM-support

group. (The first was the Eulenspiegel Society, founded three years earlier in

New York.) She also enrolled in "Dungeon Monitor" training, where she

learned safety guidelines for "play parties," including proper use of

whips and floggers and the adoption of a "safe word" to terminate

scenes.

Margot Weiss, a product of the department of cultural

anthropology and the women's studies program at Duke University, is an

assistant professor of American studies and anthropology at Wesleyan

University. In her absorbing portrait of San Francisco as "a queer Sodom

by the sea," Weiss surveys the gradual transformation of BDSM from the

"more outlaw" era of gay leathermen in Folsom Street bars of the

pre-AIDS era to today's largely heterosexual scene in affluent Silicon Valley,

where high-tech workers congregate at private parties or convivial

"munches" at chain restaurants with convenient parking lots. During

her three-year fieldwork, Weiss became an archivist for the Society of Janus,

which was founded in San Francisco in 1974 as America's second BDSM-support

group. (The first was the Eulenspiegel Society, founded three years earlier in

New York.) She also enrolled in "Dungeon Monitor" training, where she

learned safety guidelines for "play parties," including proper use of

whips and floggers and the adoption of a "safe word" to terminate

scenes.